ASM: What is the overall mission and purpose of Serve 2 Unite?

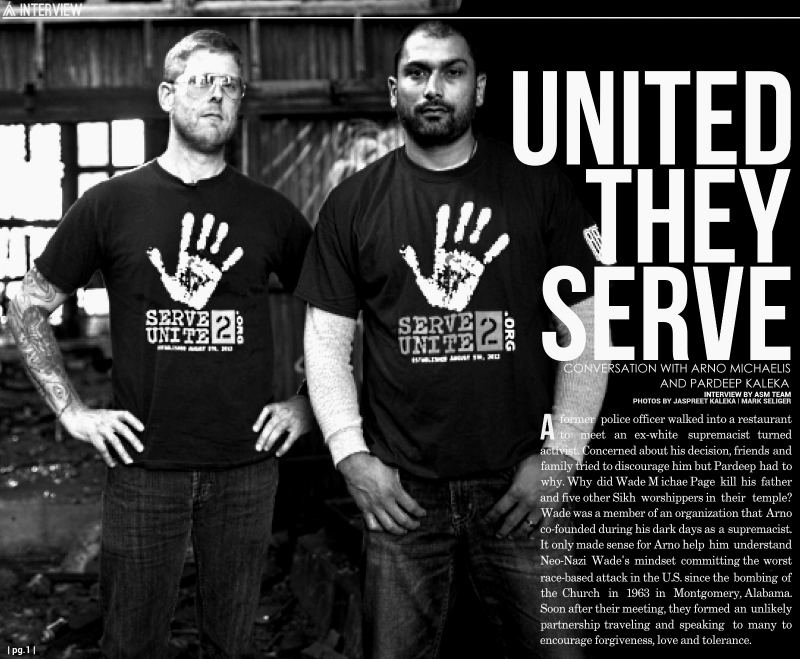

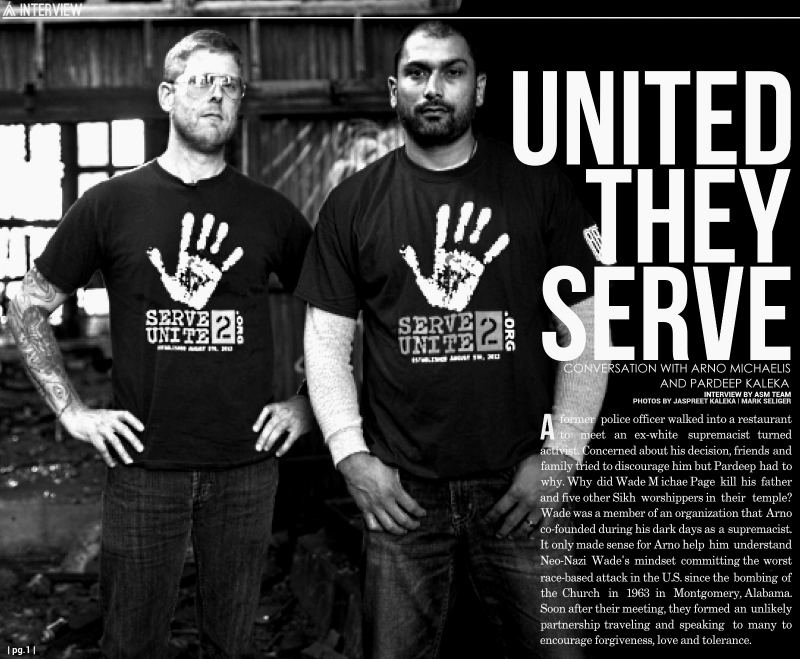

PK: Serve 2 Unite today is focused on global engagement and action. It initially started as an outreach group based in Wisconsin shortly after the shooting incident. It was sort of a youth and millennial group that could address some of the problems by using the Sikh principle of Seva or service; thereby getting our community out into the community to be proactive. That became sort of a positive community identity development using those same principles of service while aligning our community towards active global citizenship.

ASM: You mentioned ‘bringing the Seva principles out into the community.’ Before the shooting, the subsequent outreach and coming together, was the community as open as you think it could have been to the larger community, or was there more of a focus on helping one another in a closer familial bond? How did that work?

PK: Before the shooting, I think that we had a very closed-in community, though not on purpose. I think that sometimes people just get comfortable around people that they can identify with due to speaking the same language, eating the same food or dressing the same way. No matter who we are, we get comfortable hanging out with like-minded people; and most of the people that are in that community are first-generation immigrants as well. So, there is that dynamic that is playing a role. A lot of people did not know who we were, and confused us with other groups or ideas relayed by the media. We decided not to just tell people who we were but show them through our actions.

ASM: Where do you think your identity initially within this part of this community in Wisconsin came from? Was it the fact that many of you immigrated together from the same point of origin? Was it your shared religion, or was it some other force?

PK: I think we all, no matter who we are, unlocked the door for each of us though with a different key. For me personally speaking, I came here in 1982 at the age of six; and I am a first-generation immigrant who formed myself immediately within the southeastern Wisconsin community. There was no ability for me to identify myself too much with any group as it was. I wondered about this, in addition to the feeling of never being enough and it saddened me. I relied on some level that this is true to a degree for everybody - especially growing up in this community. Growing up was an act of slowly discovering where one fits in; and for me, this process was an inspiration for continual growth. As I got older, I looked at those things as a positive, which enabled me to be a part of the culture that I am a part of. Nowadays this can scare people because they think that they are being inauthentic. I felt I was cursed growing up because I could not fit into any group, but now I really embrace it. This is why I appreciate being interviewed by an African magazine.

ASM: Arno, we know you critique the question of identity. Knowing that you have been through several phases, when was it that you began in your first or second stage to identify as a white man as opposed to an American or a Human -- how did that formation of identity begin?

AM: That was really an extension of my frustration and rebellion. I grew up in an alcoholic household and got the reputation as a troublemaker, which I liked. As a teenager, I began drinking and became antisocial identifying myself as a skinhead for a few years. To me it was about defying society or breaking things. Interestingly, there is a range of identity that people get from punk rock when I was making music. It may be hard to believe but those who are antisocial and hostile to people, see themselves as activists. And I certainly gravitated towards the hostile end of the spectrum and in that frame of mind, I got introduced to the white power narrative through the skinhead music. It was in that narrative I felt like a hero because of the capability to be someone fighting for his people against this underlying genocide that was happening against the white race. As ridiculous as that all sounds, but for an angry antisocial kid who felt disconnected from his family, school and society, the narrative had a lot of appeal to it. That is how I started identifying myself not only as a white man but as a white warrior who was fighting for his people.

ASM: We understand thoroughly being Africans and an African American, there can be a struggle to connect with people on some level that is not automatic, but did not know there are Caucasians who would also feel disenfranchised from the culture as well. It is an interesting parallel. Would you describe your search for identity as looking for a connection of some sort?

AM: I think that is a good or proper interpretation. A lot of this really had to do with my personality and the circumstances that I grew up in - which by no means were arduous. I lived in a nice house located in a nice neighborhood. I never took a beating nor did I have a rough childhood. I am sure there are probably many who would have happily traded childhoods with me in that area. However, there was alcoholism and emotional violence in my house; combined with my personality type as an alcoholic and an adrenaline junkie, I did not feel comfortable going along with the flow because of the need to walk back against the prevailing winds. Interestingly looking back as a teenager in the late ’80s, I saw the status quo as one of multiculturalism. This is a common thing with any extremists, especially with white supremacists. There is a real historical myopia if one is looking at what is right in front of him or herself without having any kind of understanding of how we got to where we are. So I did not see the struggles for multiculturalism or its great merits – though white kids began listening to hip-hop artists such as Nas, N.W.A amongst others, in addition to seeing the United Colors of Benetton billboards with diverse models representing a greater range of humanity than most of us had ever known.

ASM: How did your transition begin? What were some of the things that made you start to examine whether this was the way you wanted to go?

AM: The simple answer about my transition is that it is an exhausting thing maintaining that sort of anger because it is work. It is an insatiable desire that can never be met so you will never feel comfortable nor at peace. But you think that the hate and the violence are a means to something but they are not because you are closed to the beauty of the world. You think that you can rid yourself of the violence to bring about a better day. You dream that you are a selfless warrior who is going to fight the forces perceived to be against you. However, it is such a futile pursuit, because so much of it comes from within. At the same time as I attacked innocent people, I knew it was wrong because deep inside, the humanity in me was humiliated at the way I was acting; but I did not have the courage to answer that inner voice or to be accountable to it - and that caused further exhaustion, which came from many directions. It came from cutting myself off from the rest of society because when you adopt a violent extremist mindset, you isolate yourself in service to it. So, as a white supremacist I could not take in anything that was not in line with my beliefs including music, television, film, newspaper and more. So even though I always loved music and culture, it was hard to reconcile those parts of myself.

ASM: Were there any outside influences that could directly affect you during these times?

AM: The most exhausting was when people who I desperately tried to hate treated me with kindness. I was very fortunate that during that seven-year period there were many instances where a Jewish boss or a lesbian supervisor or black and Latino co-workers treated me as a human being when I least deserved kindness and respect. And while those acts of kindness did not change me on the spot, they did plant seeds that made it difficult to maintain the level of ignorance to hate and hurt people.

ASM: When did you start looking towards activism? How long and how did that transition begin? Was there an immediate break and a switch? What were some of the personal changes that you remember from this era of your life?

AM: That took a while. I left the movement as we called it, in 1994. It was a gradual process that began formally in 1993 - going from being entrenched in leadership to being a complete outsider. Socially within those years, instead of all white power rallies, I was at warehouses on the south side of Chicago dancing to house music with some of the most diverse people you can ever imagine. The people in that new counterculture loved me unconditionally; they accepted me and it demonstrated that there is a whole different life that I had never comprehended. Regarding my personal changes, it was difficult initially. Without the alcohol to numb the regret of my past, I fell into a deep depression. I was suicidal but at that point I had a daughter and her presence really helped bring me out of that. She was a light and an inspiration. That is when I started writing and attended college from 2007 to 2010. The process brought me to 2010 where I came forward with my story on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. day – that began my activism.

ASM: Pardeep you mentioned growing up asking for identity and looking for different places where you might fit in. Did you also become socially or politically active at that time?

PK: Yes. As Arno mentioned, during the early ’80s there was a push towards multiculturalism and the consistent spread of the notion that we are all Americans within a melting pot. In so doing, you lose some of yourself and some of what you grew up with; thereby accepting American values that in some way could connect you with everyone who had made the similar choice. When we emigrated to America, my parents learned English. Not only did it feel like we were forgetting about the language that we knew, it was also about the way one dressed, talked or walked. Though we lost some of that, I do not think it really changed who we were as people. There is temptation to forget history and to abandon culture, but what we see now is that it can be detrimental to the society. We lose pieces of the precious human tapestry that can broaden our ability to love and experience the world. I had to rediscover who I was and what my culture meant to me. A lot of it comes back to some of the fundamental principles of Sikh that is called Chardi Kala, translated to mean ‘relentless optimism.’ It is something that I heard consistently at the temple but it faded into the background of thinking. I do not think I understood what it meant until the aftermath of 2012 - I realized that it had become a significant part of me. This was a cultural principle that would be the basis of what would become our organization ‘Serve 2 Unite.’ When I met Arno, the inspiration to become a catalyst for a real connection and understanding came to fruition because as he spoke, I really wanted to understand the why, because I did not just want to conjecture up assumptions – I needed to hear it from somebody. Arno was brave and gracious enough to really open up and explore that. We opened up a dialogue and shortly after that we began to grow together through the principles of Sikhism.

ASM: The connection between any different people seems to imply optimism because it might not work out. What are some of the benefits of taking that risk? What are some of the things that you both have gained working together versus working individually within your communities of origin?

PK: Well, for me, I realize that relentless optimism is an everyday process. In choosing to trust, we are taking back power. Sometimes we misinterpret what power, compliance and justice mean; and we sometimes do not understand the role that forgiveness and compassion play. Once we began working together, we thought hard about the basics of communication, sharing experiences because when you try to parse details of one past or another, things can be misinterpreted. But when we began to think about unreserved forgiveness, pure compassion and basic love, that is when change begins. One of the images from that day in my mind is the number 14 that was tattooed on the shoulder of the Wisconsin shooter. As strange as it may seem, it was very personal for me because one of the ways I assimilated into the American culture was through sports so I had a strange connection identifying with something like that. You can say it was a glimmer of hope or optimism because I could somehow see something innocent about this person. In fact, the number was on my jersey I wore growing up. One of the questions that I asked Arno the first time we met was the number’s symbolism. He explained it symbolized a fourteen-word code that supremacists used to solidify their commitment not to assimilate. Understanding that, and somehow still holding a place of love and forgiveness, I began to really internalize the need for, and the power of truly relentless optimism.

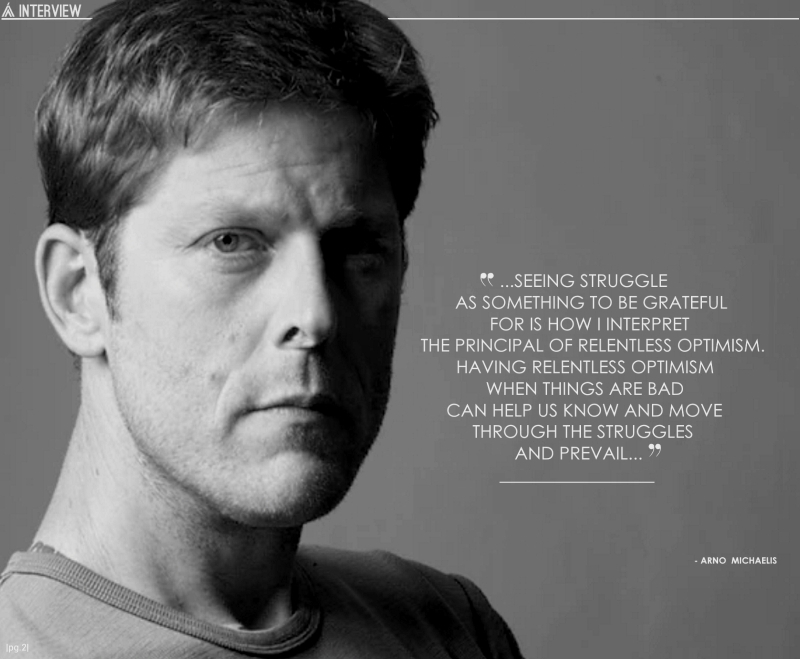

AM: Seeing struggle as something to be grateful for, is how I interpret the principal of relentless optimism. Having relentless optimism when things are bad can help us know and move through the struggles and prevail to be able to help pull others through their struggles as well. There is value in that experience.

ASM: Have you seen a pushback from within your communities of origin? What is your reaction to people who are still in that stage of their lives clinging hard to an exclusionary identity? How do you feel when you meet people of different backgrounds that also have that attitude towards you? Is there a way you approach it?

AM: Well, as far as my old buddies are concerned, it struck me early on that I really have the hardest time practicing what I preach with them. When I see skinheads or Klan members, I fear my reaction and it sucks. When I see people who are like that, I am really experiencing who I was and it is very uncomfortable; but it should be uncomfortable for me because I did a lot of harm to the world, and I must be accountable to that. The first thing I focus on is the need to give them the chance to change for the better because people gave me the chance. If you do not give them that chance, the odds of them changing for their own lives and those around them become a lot slimmer. So I welcome my old buddies as a challenge and as a way to challenge myself to see them not with reactive hate, but as people who need help. To anyone who may be skeptical of who I am, I say join me in my work. The first speaking engagement I did when I was invited to speak in front of a predominantly black audience, I remember a 90-year-old man who came up to me and thanked me for giving him hope. I thought about everything that he must have seen and gone through. For him to say that to me was one of the most amazing uplifting things that had come to me up to that point. Yet right after him, a younger man noted that he was not sure if he could really buy into my new-found journey however, he did commend my efforts. I did not blame him and I told him so, for I have done things that would make any reasonable person doubt what I say. I deserve to be doubted and scrutinized - I welcome it. It helps me be a better person. It helps me do the work that I do more effectively. I think scrutiny is a good thing because it makes me better.

ASM: Returning to the principles of optimism, service, kindness, gratitude and forgiveness, can you see these principles being transposed onto groups or organizations that are larger than single people?

AM: If we do not have a firm foundation of kindness, gratitude and forgiveness, we really do not stand a chance at solving the seemingly larger problems between groups and nations. Many like to butt heads on policies such as capitalism versus socialism or justice versus freedom and they are conversations we need to have; however, if we do not work to build our solutions from the basis of kindness, gratitude and forgiveness, then we cannot have those conversations successfully. Those conversations will lead to more strife than healing and togetherness. So, I truly concentrate on creating a space to have those conversations with a principled foundation. I think that if you move from that space, you can absolutely succeed.

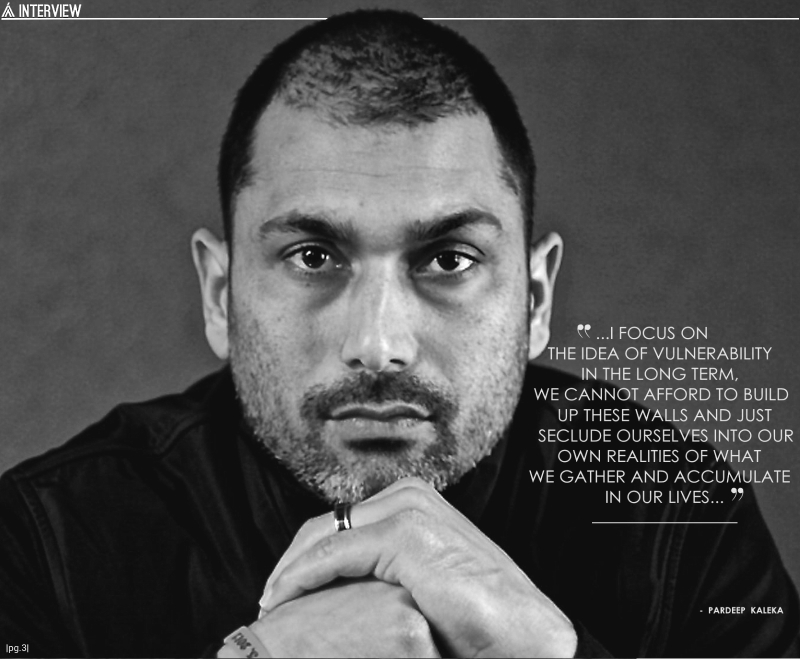

PK: For me, I focus on the idea of vulnerability. In the long term, we cannot afford to build up these walls and just seclude ourselves into our own realities of what we gather and accumulate in our lives. A lot of times the reason we hold onto to seclusion and abandon the melting-pot mentality is because we operate under the illusion that we own the things that we have. We think that we control and protect them - be they positions or races, or other things we may identify with. Until we face the idea that we are sharing these things because sharing is the basis for our very existence, will we see any real betterment happen. We need to understand that who we are is connected to each other and our claims and actions do not stop with us, but ripple on through this shared experience.

ASM: What is your vision of the future moving forward? Do you imagine Seva as something that people can expand to change the world and culture on a macro level, or is it something confined to small communities? Also, if there is one thing you could ask people to think about before they consider lashing out violently, what do you think that would be?

PK: I think that we have been able to reach a lot of the southeastern Wisconsin community, and it is great to touch people at an individual level. We are already seeing that this is growing to be much bigger than we initially thought, and that has changed the paradigm and reality. We notice after the presentations we give, three to four kids line up wanting to connect; in some cases, stating how they felt before they met us. In paying close attention to them, it often came back to a trauma that they were going through. So, over the past year we have been working with different communities to address some of those reoccurring traumas. We work with survivors and perpetrators of abuse and assault with the aim of changing the paradigm behind the way that they perceive not only their suffering, but the world as well. It is something that can expand, but will remain rooted in the deeply personal experiences of individuals. It is scalable because when you change one person, you change the entire world as seen through their eyes.

AM: Regarding the second part of your question, there have been scientific studies that deconstruct what composes happiness. It has been found that gratitude and forgiveness are what compose happiness; and I honestly believe that to the depth of my being. As I look back on my life, I see what went wrong. It was because of the failure to practice and engage with those things on my part; however, everything that went right was because I successfully engaged with those aspects of our humanity. Daily, I remind myself to stay present in a mindset of kindness, gratitude and forgiveness because these will set a foundation for my own happiness, and make the world around me a better place. Those things are very contagious. When we are kind to people, they are far more likely to be kind to others. The same goes for gratitude and forgiveness. I believe the more of those three qualities we have in our society, the more able we will be able to address these seemingly insurmountable rifts between people.