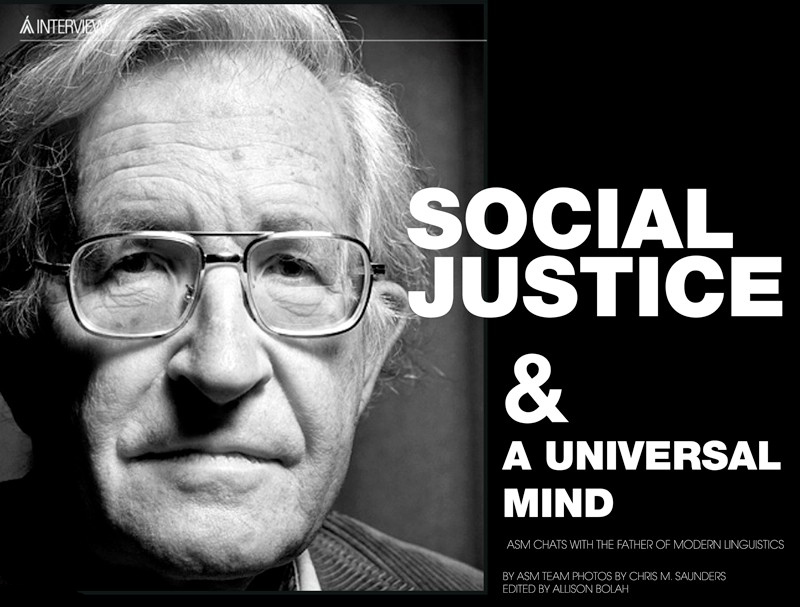

For more than a decade, Noam Chomsky reigned as the world's most cited thinker within the fields of Arts and Humanities. Often referred to as the “Father of modern linguistics,” he is a philosopher, cognitive scientist, logician, political critic, and social activist. He is an institute professor and professor (emeritus) in the Department of Linguistics & Philosophy at MIT, where he has worked for more than fifty years. In addition to his work in linguistics, he has authored over one hundred books, covering war, politics, and mass media. ASM had the pleasure of chatting with Mr. Chomsky, and learning more about what ties our minds together, and how that knowledge drove him to seek social justice for the least amongst us.

ASM - You are famously associated with the idea that there's a universal deep grammar behind language. Would you explain the concept briefly for those of us who are not familiar with it?

Chomsky- First of all, the term universal grammar has a traditional meaning. But in the Modern period, roughly the last half century, it's been used in a technical sense, which is similar to but different from the traditional meaning. So universal grammar traditionally meant properties that are common to all languages. But universal grammar in the Modern sense means the genetic component of the language capacity. That is whatever it is about humans but say not chimpanzees or songbirds or cats or whatever that enables an infant to quickly and reflexively identify the parts of the environment that are language-related and then to proceed in a very systematic and regular way to attain very quickly, in fact, the capacity we're now using. That's a special human characteristic. If you put, say, a chimpanzee in the same environment, it wouldn't even take the first step. It can't identify the language-relevant elements from noise. And it's not because it lacks the sensory capacities, it has approximately the same sensory capacities, but it just doesn't have the internal, basically, computational capacities that enable it to do it just as we can't do things a chimpanzee can do. So it's a special human characteristic. We have pretty good evidence that it developed recently in the human species, recent in evolutionary time; this is roughly within the last 100k years, so long after the separation from any other species. So there’s really no analogue in other species. And we have very good evidence that the capacity has not changed for at least fifty to seventy-five thousand years. That is the time since our ancestors began to leave Africa. There's very strong evidence that human origins are in Africa about fifty thousand years ago. The trek from Africa started very quickly, spread over the whole world. And there's very strong evidence that humans everywhere have virtually or maybe identically the same language capacity. What that means, for example, is that if you take an infant from some Amazonian tribe where they haven't had contact with other humans for maybe thousands of years and you bring that infant to say, New York, it'll speak just like any kid in New York and conversely. Not every case has been tested, but the evidence is overwhelming. Which means that whatever this capacity is, it was fixed before the departure from Africa. Not too long before that it doesn't seem to have existed at all as far as the archeological and other evidence indicates. So it seems to have some how emerged very quickly in some small window of time. We can investigate its properties just by looking at the properties of human language, what kinds of variations there are, how it's acquired, and how it's used. By now it's possible to discuss… what's going on in the brain when language is used and understood. And that's essentially the study; it's like the study of the human visual system; It's like an organ to humans and it's essential,- there's nothing to compare it with elsewhere. And you try to find out its properties. Well, any such system has, is determined somehow by our genetic endowment. And universal grammar in the Modern sense is just the name for that genetic basis whatever it is.

“…There's very strong evidence that human origins are in Africa. The trek from Africa started very quickly, and spread over the whole world. And there's very strong evidence that humans everywhere have virtually or maybe identically the same language capacity…”

ASM - Is there a relationship between this language capacity and our thoughts? Does it create in some ways the way we conceive the world?

Chomsky - Well, you know that's a traditional question that goes back to classical times. That's a very hard question to study. For one thing, although we can characterize pretty well what language is, we really don't have much of an independent characterization of what thought is. Most of what we know about thought is language-dependent. And insofar as it's language dependent, we can't investigate the relation between language and thought. So you can only investigate it to the extent that you can say something independent about thought and that's not so simple. In fact, it's not even clear that it's an easily identifiable topic. So, what we can say is that language is used typically as an expression of thought and that something's going on inside us that we call thought, and we can get various bits of evidence about it, the richest parts of which actually come from language.

ASM - Would this give you a picture of different languages having different types of thoughts?

Chomsky - There's again an old question that's called the Whorf Hypothesis that the language you speak determines how you think about things. It sounds plausible superficially but it's been very hard to find any convincing evidence of it. There are some things about effects on perception, which maybe are correct, but it doesn't seem to reach very far. It's as though people's thinking is pretty much the same whatever language they speak. There are some quite interesting investigations of these topics. Some of the best work by a friend a colleague of mine Kenneth Hale a very fine linguist who died a few years ago who was a specialist on Aboriginal languages. He was one of the founders of the modern studies of Australian Aboriginal languages and worked on American Indian languages and many others. One of his most interesting papers about thirty years ago was on what he called Cultural Gap. He investigated apparent differences, what looked like pretty radical differences, among different languages and concluded that they basically are superficial if they exist at all. For example, many languages don't have numbers, maybe numbers up to three or four, but not like our system where you can go on indefinitely. It had been thought that they don't have number concepts. But his work showed that they have exactly the same number system that we do, they just express it in other ways. For example, instead of saying 'five', they may hold up a hand and have various other ways of doing it. He also pointed out, he's worked extensively with these various tribes, and he said as soon as they move into a market system where you've go to trade they do it with no problem at all which means that they've got the whole system internalized. He also studied color words. There are many languages that seem to have very few color words, maybe just two, black and white. But he showed, I think convincingly, that they just have other ways of talking about color. So instead of red, they might say, blood or something. And again, the whole range of colors that we all have seems to be uniform. And he looked at much more subtle aspects, too, and I think made good arguments that's basically the same. Now, these are open questions. There's a lot to investigate. And there has been pretty intensive study of these questions for maybe fifty, sixty years. And the results on differences are pretty thin. So maybe there's something to it, but we're hard put to say just what it might be if anything. I mean, the striking conclusion is about human uniformity.

“…what that means is that normal human language is constantly innovative without limits. We can produce and understand an unlimited number of expressions…”

ASM - Is there's something in this discovery, or the theme of universality in your scientific work that has influenced your trend toward political action, and seeking justice for people who are apparently very different.

Chomsky - I was a political activist long before I ever heard of linguistics. My first political articles were as a child. In fact, one of them I remember because of the date. It was in February of 1939 right after the fall of Barcelona. I was a 10-year old kid writing , for the Fourth Grade newspaper about the spread of Fascism in Europe, which was at the time very obvious. I was all involved in all kinds of activism throught childhood. I later learned about linguistics. But, as I studied more and got into the kinds of questions we’re talking about, such as the questions of the universality and commonality of human beings on a deep level and the cognitive system; meshed with the things I thought about social political systems of relations among humans. I later learned that the history of thought had to some extent been speculated about in earlier centuries. There's a fundamental aspect of human intellectual capacity and it shows up very dramatically in language, which has sometimes been called its creative aspect. This was a major issue in 17th century philosophy. Language has that creative aspect. What that means is that normal human language is constantly innovative without limits. We can produce and understand an unlimited number of expressions. And, furthermore, the use of language is not determined by the circumstances, or as far as we know, even internal states. It's appropriate to circumstances, but not caused by circumstances. That's a crucial distinction and very different from anything we know about other animals. Well, this creative capacity is quite significant; it tells us a lot about humans. If we understood it better, we'd have a great deal of insight. And it's possible, you can argue from that, that's not a real logical argument, that the need for free, independent activity under one's own control in association with others is a core element of human nature. Actually, that's the big principle that underlies a good bit of Enlightenment thought about human nature and proper society and enters quite directly into the Anarchist tradition. It leads very quickly to the idea that any institutional structure in human society, whether from a patriarchal family up to international affairs, is basically illegitimate if it interferes with these fundamental aspects of human nature, free inquiry, free creativity, control of your own actions and so on. And then you can spin out of that a variety of thoughts about how human life and social arrangements, everything again from families to international affairs, ought to be organized. But, notice that these are not scientific conclusions. They're not even logical connections. They're just plausible arguments, maybe convincing, maybe not. We don't understand enough about human beings and their nature to really bring this to the domain of science.

“…the language you speak determines how you think about things, sounds plausible superficially but it's been very hard to find any convincing evidence of it…”

ASM - Are there places in Africa where you can identify in this kind of casual way the creative capacity of human beings being stifled? What major issues and sort of structures would you focus on?

Chomsky - I think it's universal in Africa, Europe, Asia, -everywhere. And you see it with young children. Children want to explore, to create but often their capacities are curbed and constricted by outside constraints. But anyone who's ever dealt with young children just knows this. That's what they're like. And this seems to go on through life. So, it's the most satisfying work an adult can do is creative independent work under one's own control. And it could be true of a carpenter, it could be true of a cook, it could be true of a scientist. That's what we strive for and enjoy and do when we can. In fact, there's kind of a nice description of this by a major 18th century figure Wilhelm von Humboldt, one of the founders of Classical Liberalism. He pointed out, and I think he's right, that if an artisan produces a beautiful work on command, that we may admire what he does, but we will despise what he is, not a free, independent person, but rather a tool in the hands of others. And I think that's pretty deep seated. All through the labor history, the history of social organization, it's true of any non-Western society that I know anything about, and I suspect it's just instinctively human.

ASM - You strike us as somebody who's very passionate. Nobody works as long as you have and as hard as you have without deep, personal passion for the cause that they're working on. Was there a moment in your life that you recall this sort of passion sort of being ignited?

Chomsky - I think we're all born with it. As I said, if you deal with young children, you see it all the time. It often gets constrained and restricted and curbed in some way. In fact, a lot of the school system has that effect. Many aspects of later life are designed to have that effect, to control and restrict. But, I think I was just lucky, I was able to escape it, to a large extent, as much as I could. But, I don't think I'm any different from anyone else.

ASM - Thank you very much. Now we can say we have a better understanding of your passion. As children of immigrants, there's a certain passion for people who are trying to create a new world in a whole new environment. We do appreciate your voice.

Chomsky - That's good to know. I am very pleased to have a chance to talk to you.