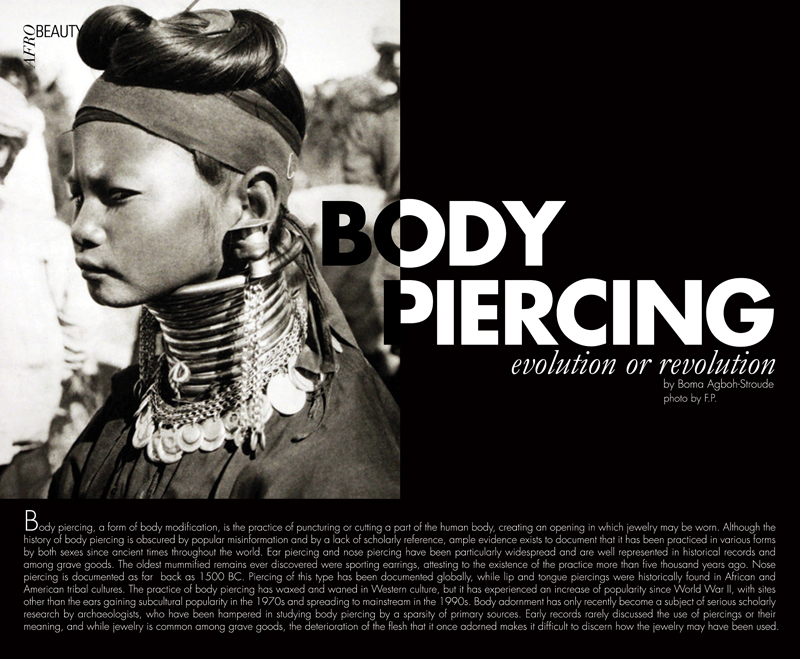

Body piercing, a form of body modification, is the practice of puncturing or cutting a part of the human body, creating an opening in which jewelry may be worn. Although the history of body piercing is obscured by popular misinformation and by a lack of scholarly reference, ample evidence exists to document that it has been practiced in various forms by both sexes since ancient times throughout the world. Ear piercing and nose piercing have been particularly widespread and are well represented in historical records and among grave goods. The oldest mummified remains ever discovered were sporting earrings, attesting to the existence of the practice more than five thousand years ago. Nose piercing is documented as far back as 1500 BC. Piercing of this type has been documented globally, while lip and tongue piercings were historically found in African and American tribal cultures. The practice of body piercing has waxed and waned in Western culture, but it has experienced an increase of popularity since World War II, with sites other than the ears gaining subcultural popularity in the 1970s and spreading to mainstream in the 1990s. Body adornment has only recently become a subject of serious scholarly research by archaeologists, who have been hampered in studying body piercing by a sparsity of primary sources. Early records rarely discussed the use of piercings or their meaning, and while jewelry is common among grave goods, the deterioration of the flesh that it once adorned makes it difficult to discern how the jewelry may have been used.

The Ear Pierce

Ear piercing has been practiced all over the world since ancient times. There is considerable written and archaeological evidence of the practice. Mummified bodies with pierced ears have been discovered, including the oldest mummified body discovered to date, the 5,300 year-old Ötzi the Iceman that was found in a glacier in Austria. Earrings are also referenced in connection to the Hindu goddess Lakshmi; and were found in a grave in the Ukok region between Russia and China dated between 400 and 300 BCE. Among the Tlingit of the Pacific Northwest of America, earrings were a sign of nobility and wealth, as the placement of each earring on a child had to be purchased at an expensive potlatch. Earrings common in the eighteenth dynasty of Egypt generally took the form of a dangling, gold hoop, while gem-studded golden earrings shaped like asps seem to have been reserved for nobility. The ancient Greeks wore paste pendant earrings shaped like sacred birds or demigods, while the women of ancient Rome wore precious gemstones in their ears. In Europe, earrings for women fell from fashion generally between the fourth and sixteenth centuries, as styles in clothing and hair tended to obscure the ears, but they gradually thereafter came back into vogue in Italy, Spain, England and France—spreading as well to North America—until after World War I when piercing fell from favor and the newly invented Clip-on earring became fashionable. According to Philip Stubbs author of The Anatomie of Abuses, earrings were even more common among men of the sixteenth century than women. It is noted that Raphael Holinshed, an English chronicler in 1577, confirmed the practice among lusty courtiers and gentlemen of courage. Evidently originating in Spain, the practice of ear piercing among European men spread to the court of Henry III of France and then to the Elizabethan era in England, where earrings (typically worn in one ear only) were sported by such notables as Robert Carr, 1st Earl of Somerset, Shakespeare, Sir Walter Raleigh and Charles I of England as well as the common men. From the European Middle Ages, a superstitious belief that piercing one ear improved long-distance vision led to the practice among sailors and explorers. Sailors also pierced their ears in the belief that their earrings could pay for a Christian burial if their bodies washed up on shore.

The Nose Pierce

Nose piercing also has a long history as The Vedas, the sacred scriptures of Hinduism, refers to the goddess Lakshmi's nose piercings. However, modern practice in India is believed to have spread from the Middle Eastern nomadic tribes by route of the Mughal emperors in the 16th century. Sometimes done the night before a woman marries, it remains customary for Indian Hindu women of childbearing age to wear a nose stud, usually in the left nostril, due to the nostril's association with the female reproductive organs in Ayurvedic medicine. Nose piercing has been practiced by the Bedouin tribes of the Middle East, the Berber and Beja peoples of Africa, as well as Australian Aborigines. Popular among the Aztecs, the Mayans and tribes of New Guinea was the septum piercing in which pierced noses are adorned with bones and feathers to symbolize wealth and (among men) virility. In addition, gold septum rings are adorned the Aztecs, Mayans and Incas- a practice continued to this day by the Kuna of Panama. Nose piercing still remains popular in Pakistan and Bangladesh and is practiced in a number of Middle Eastern and Arabic countries.

“...it remains customary for Indian Hindu women of childbearing age to wear a nose stud, usually in the left nostril, due to the nostril's association with the female reproductive organs...”

The Lip And Tongue Pierce

Lip piercing and lip stretching were historically found in African and American tribal cultures. Pierced adornments of the lip or labrets were sported by the Tlingit Indians; the peoples of Papua New Guinea, Amazonia, Aztecs and Mayans; while the Dogon people of Mali and the Nuba of Ethiopia were known to wear rings. The practice of stretching the lips by piercing them and inserting plates or plugs was found throughout Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and South America as well as among some of the tribes of the Pacific Northwest and Africa. In some parts of Malawi, it was quite common for women to adorn their lips with a lip disc called a pelele which by means of gradual enlargement from childhood, could reach several inches of diameter and would eventually alter the occlusion of the jaw. Such lip stretching is still practiced in some places. Women of the Mursi of Ethiopia wear lip rings on occasion that may reach 15 centimeters in diameter. In some Pre-Columbian and North American cultures, labrets were seen as a status symbol. They were the oldest form of high status symbol among the Haida women, though the practice of wearing them died out due to Western influence. Tongue piercing was practiced by the Aztec, Olmec and Mayan cultures as a ritual symbol. Wall paintings highlight a ritual of the Mayans during which nobility would pierce their tongues with thorns, collecting the blood on bark which would be burned in honor of the Mayan gods. It was also practiced by the Haida, Kwakiutl and Tlingit, and as well as the Fakirs and Sufis of the Middle East.

The Piercing Today

By the early part of the 20th century, piercing of any body part had become uncommon in the West. After World War II, it began increasing in popularity among the gay male subculture. Even ear piercing for a time was culturally unacceptable for women; but that relatively common form of piercing began growing in popularity again by the 1960s. In the 1970s, piercing began to expand, as the punk movement embraced it, featuring nontraditional adornment such as safety pins; and Fakir Musafar known of the Father of Modern Primitivism popularized it, incorporating piercing elements from other cultures, such as stretching. Body piercing was also heavily popularized in the United States by a group of Californians including Jim Ward, who is regarded as The Founding Father of Modern Body Piercing. Bridging the gap between self-expressive piercing and spiritual piercing, modern primitives use piercing and other forms of body modification as a way of ritually reconnecting with themselves and society, which according to Musafar once used piercing as a culturally binding ritual. However, it is noted that body piercings may also be a means of rebellion, particularly for adolescents in Western cultures.

While body piercing has grown more widespread, it still remains controversial, particularly pertaining to the youths. Some countries impose age of consent laws requiring parental permission for minors to receive body piercings. Scotland requires parental consent for youths below the age of sixteen. In addition to imposing parental consent requirements, Western Australia prohibits piercing private areas of minors, including genitals and nipples, on penalty of fine and imprisonment for the piercer. Many states in the US also require parental consent to pierce minors, with some also requiring the physical presence of the parents during the act. The display or placement of piercings have been restricted by schools, employers and religious groups. But in spite of the controversy, some people have practiced and still practice extreme forms of body piercing, with Guinness bestowing World Records on individuals with hundreds and even thousands of permanent and temporary piercings. Despite the hesitation to this form of expression, body piercing has been around for centuries and it will not disappear anytime soon. Hence our global society will have to continue to educate itself, accept and respect the fact that body piercing is a part of society or culture regardless of its evolution…or revolution.